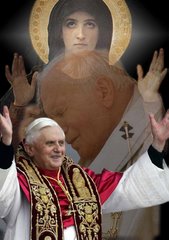

In her latest column Emily Byers praises the heroism demonstrated by Pope Benedict XVI while asking the Muslims of the world for a response to Benedict's call for dialogue.

Emily Byers on the Courage of Pope Benedict XVI

Wednesday, November 29, 2006

Tuesday, November 28, 2006

Emily Byers on the Virtue of Poverty

On November 19, 2006 Emily Byers presented to the Parousians about the virtue of poverty and how we as laity can live it out. The following is the presentation as transcribed by Emily Byers and Michael R. Denton

Fr. Thomas Dubay’s Happy Are You Poor: The Simple Life and Spiritual Freedom is a unique book which manages to be simple, challenging, and profoundly orthodox at the same time. To hear and fully grasp its message, the reader has to be open to change and ready to consciously exercise humility.

Part of the reason this book is unique is that poverty is not popular. People scoff at the idea of choosing poverty, arguing that only the most naïve would think that the poor can be truly happy.

Sometimes people preach about poverty, but not in a meaningful way. As Fr. Dubay writes, “It is popular to speak about the third and fourth worlds and to assail the injustices of nations, but this sort of oration leaves both the speaker and the listeners in their comfortable modes of life. Hence no one much objects. It is fashionable in religious circles to speak and write about joy and celebration and resurrection, and for this there are many ready ears. But it is quite another matter when it comes to penance, mortification, sorrow, suffering, and asceticism.” As a result many preachers have watered down the Gospel’s message on poverty to something bland and meaningless, as Fr. Dubay continues: “Rather than have it [poverty] mean what the Gospel says it means, namely, a materially sparing life, it is now said to be a ‘respectful use of creation’ or a ‘sharing of one’s time, person, and talent.’ These new definitions are convenient, for they exact next to nothing.” It would seem then that only lunatics could embrace poverty as a good and be happy in a state of poverty.

And yet we know that Jesus, who first said “Happy are you poor,” knew what he was talking about. Jesus himself was born into poverty when he arrived in a manger and labored as a carpenter until His ministry began. As Fr. Dubay explains, “We are too dull to utter a thought so brilliant [as ‘Happy are you poor’]. He who spoke it did know poverty from the inside. He was born into dire circumstances, and he died with absolutely nothing. In between times he chose to have no place to lay his head. He loved the poor, and he gravitated toward them. He was one of them. He was romanticizing nothing.”

So Jesus knew what he was saying, but what precisely did he say? Common misconceptions about the meaning of “Gospel poverty” abound. Gospel poverty is not carelessness, disorder, laziness, or dirt. Gospel poverty is not destitution, nor is it miserliness, or an excuse to not part with our wealth. It is not mere detachment from goods, for “poverty of spirit” will only come with factual frugality. It is not merely an “availability of person, talent, and time for others.” (This position in particular is a rather blatant attempt to rewrite the Gospel.) Gospel poverty is not insensitivity to beauty or health, instead Gospel poverty entails sensitivity to beauty and the preservation of good health. Gospel poverty is not merely a “respectful use of creation,” since this definition can easily be used to justify whatever behavior one is already practicing. Finally, Gospel poverty is not sentimentalism or merely “feeling the pain of the poor.” The Gospel is always meant to be lived as hard fact, not empty rhetoric.

Having defined what Gospel poverty is not, we can now say precisely what Gospel poverty is. First, we remember 1 Corinthians 2:9: Nothing compares to our God, and to what awaits those who love Him. That is, God ought to be our focus and nothing else. As Fr. Dubay writes, “Happiness is found not in things but in persons and especially in the Divine Persons…We are to be head over heels in love with God… People in love are not much concerned with things. They are person oriented, not thing centered. A consumerist is not in love.” Since love for people and for God particularly ought to be our focus, a desire for things can only hinder us in the pursuit of relationships with people and God.

Jesus reiterates this in Luke 16:33, when He said, “No one can serve God and mammon.” Note that there is no compromise here; Jesus is not asking that you serve God mainly while serving mammon sometimes. He is asking instead for a “totality of pursuit,” that is, He is asking that we give him everything at all times. To do this we need to be detached from all we possess just as we need to love with our entire selves.

To be detached, we need to view possessions in their proper place. Too often we see them as ends in and of themselves when in fact they are merely means to greater ends. John 4:34 and Colossians 3:1-2 indicate that those focused on the kingdom see all things as means only, because Earth is not our home. We are strangers, nomads, and as Hebrews 11:13-16 says, “pilgrims in search of our real fatherland in heaven.” This is a radical teaching in the society we live in. Fr. Dubay recognizes this, yet does not shirk the call to poverty. He writes: “Understanding Gospel poverty perfectly requires a perfect conversion, a 180-degree switch from worldliness.” In this there is no compromise. If we cannot accept the ideas of the Gospel, we cannot hope to live a lifestyle of factual frugality.

It seems then that we are called to poverty, but why should we be happy about it? The world associates poverty with unhappiness and wealth with happiness, and so many feel that in order to achieve happiness some type of compromise is necessary. As Fr. Dubay says, “By all standards of this world these four words [‘Happy are you poor’] are intolerably false. They seem to be an insult to the billions of human beings at this moment enduring the slow, grinding torture of empty stomachs, cold nights, crawling vermin, lingering insecurity, gnawing idleness, premature death.” Despite the fear such images invoke in us, we must learn to be poor in spirit and in fact.

Material wealth and the pleasures of the world only leave us more dissatisfied. The Gospel is not easy, for it calls us to a paradox: we must embrace a certain asceticism but also a rich, abundant life in Christ. To do this we must make Gospel poverty concrete in our daily lives so that to others Gospel poverty translates factually as well as spiritually. So the question, especially for the laity and those who must support a family, is how to do this practically? If factual poverty is not hunger or destitution, what is it?

It seems too hard for us to embrace the poverty of St. Francis of Assisi, but Scripture about poverty (as does all Scripture) applies to every person in every vocation, including the married or single as well as priests and religious. This seems “outrageous” to today’s world, Fr. Dubay admits… and yet, “frugal living is a religious ideal,” one we must all desire.

So what can the laity do? Fr. Dubay lays out several guidelines for the laity to achieve what is required by Gospel poverty. The first is to have “Value Motivation,” which means that we must pursue poverty for the right reasons, namely for what poverty makes possible: a “radical readiness for the divine word,” the “freedom to live a sharing-sparing lifestyle” and “apostolic credibility.”

The second is to maintain one’s state, that is, to avoid superfluities without neglecting one’s duty to one’s family. To do this, it is very helpful to look to the lives of the lay saints. St. Thomas More and Elizabeth of Hungary provide great examples. St. Thomas More was known to spend lavishly only on two things: the education of his children, and a zoo that he kept both for study and because he knew that his children and visitors were greatly entertained by the animals. St. Elizabeth of Hungary spent money on dresses, but only because she saw that seeing her wearing them greatly pleased the husband to whom she was devoted. She still managed to use much of her time and money helping the poor and so managed to be a sign of Gospel poverty to the world.

It is very important that as we live the Gospel poverty, we serve a sign of poverty to the world and challenge its preoccupation with possessions. To do this our poverty must be visible through a simple lifestyle that contrasts, even clashes with the status quo of the world. As Dubay writes, “The deeply converted layman is different from the large majority of his counterparts. He is a challenge in the flesh. Not that he preaches daily homilies in shop or office. But he must be different—and not all will like the difference. Though he is living in this world, his center of gravity is not on earth; it is in the bosom of the trinity.” This sort of life is what Dubay refers to as “Saintly Radicalism,” which means offering countless small sacrifices each day. That might mean skipping your customary cup of coffee, or taking a cold shower or giving up anything which, offered as a sacrifice, could help you focus on God. The best way to see how to do this is to examine the lives of the saints, especially the lay saints, and to practice serious self-examination.

Self-examination is neither popular nor easy, but it is essential to spiritual growth. One of the best ways to examine our lives is to learn to identify things as either necessities or superfluities. The things we buy and own may or may not be necessary depending on what our goal is and where our center lies. If our goal is with God, then things are necessary if and only if they help us to grow closer with God. That which is necessary can be divided into two categories: ends and means. Ends are things sought for because they are good in themselves and nothing can justify being without them. Examples include God, knowing, and loving. Means are necessary only when we must have them to reach one of the aforementioned ends.

A superfluity, on the other hand, is needed neither for itself nor as a means to an indispensable end. As Fr. Dubay puts it, “Pursuing a superfluity is pursuing a dead end.” To live Gospel poverty we must then rid ourselves of superfluities and concentrate on those things which are necessary for union with God. To do this we must ask ourselves a few questions. Fr. Dubay offers sixteen of them, but a few really stand out:

“Am I happy when at times circumstances require me to go without a necessity?” For example, when things break, like the hot water heater or our computer, do we curse about the burden or do we thank God for the opportunity to live more simply?

“Do I give to the poor not only from my superfluities but also from my need?” Jesus said that the woman who gave her last penny away was the most blessed. We need to ask ourselves if we are following that example, or if we only give what we can spare.

“Have I practically [in practice] embraced the consumerist philosophy of ‘the good life’? Do I consider myself as called to witness against this philosophy by a sparing-sharing manner of life?”

“Am I vain in my dress…my home…my other possessions?”

“Can I conclude from my manner of life that my center of gravity is not in this world? Does my use of creation speak of God to them?”

In closing, the exercise of the virtue of poverty, as outlined in the Gospel and evidenced in the lives of the saints, naturally flows from all we have come to know and understand in our faith. We cannot, in good conscience, ignore this crucial element of the Christian life, because we cannot achieve true holiness without it.

Fr. Thomas Dubay’s Happy Are You Poor: The Simple Life and Spiritual Freedom is a unique book which manages to be simple, challenging, and profoundly orthodox at the same time. To hear and fully grasp its message, the reader has to be open to change and ready to consciously exercise humility.

Part of the reason this book is unique is that poverty is not popular. People scoff at the idea of choosing poverty, arguing that only the most naïve would think that the poor can be truly happy.

Sometimes people preach about poverty, but not in a meaningful way. As Fr. Dubay writes, “It is popular to speak about the third and fourth worlds and to assail the injustices of nations, but this sort of oration leaves both the speaker and the listeners in their comfortable modes of life. Hence no one much objects. It is fashionable in religious circles to speak and write about joy and celebration and resurrection, and for this there are many ready ears. But it is quite another matter when it comes to penance, mortification, sorrow, suffering, and asceticism.” As a result many preachers have watered down the Gospel’s message on poverty to something bland and meaningless, as Fr. Dubay continues: “Rather than have it [poverty] mean what the Gospel says it means, namely, a materially sparing life, it is now said to be a ‘respectful use of creation’ or a ‘sharing of one’s time, person, and talent.’ These new definitions are convenient, for they exact next to nothing.” It would seem then that only lunatics could embrace poverty as a good and be happy in a state of poverty.

And yet we know that Jesus, who first said “Happy are you poor,” knew what he was talking about. Jesus himself was born into poverty when he arrived in a manger and labored as a carpenter until His ministry began. As Fr. Dubay explains, “We are too dull to utter a thought so brilliant [as ‘Happy are you poor’]. He who spoke it did know poverty from the inside. He was born into dire circumstances, and he died with absolutely nothing. In between times he chose to have no place to lay his head. He loved the poor, and he gravitated toward them. He was one of them. He was romanticizing nothing.”

So Jesus knew what he was saying, but what precisely did he say? Common misconceptions about the meaning of “Gospel poverty” abound. Gospel poverty is not carelessness, disorder, laziness, or dirt. Gospel poverty is not destitution, nor is it miserliness, or an excuse to not part with our wealth. It is not mere detachment from goods, for “poverty of spirit” will only come with factual frugality. It is not merely an “availability of person, talent, and time for others.” (This position in particular is a rather blatant attempt to rewrite the Gospel.) Gospel poverty is not insensitivity to beauty or health, instead Gospel poverty entails sensitivity to beauty and the preservation of good health. Gospel poverty is not merely a “respectful use of creation,” since this definition can easily be used to justify whatever behavior one is already practicing. Finally, Gospel poverty is not sentimentalism or merely “feeling the pain of the poor.” The Gospel is always meant to be lived as hard fact, not empty rhetoric.

Having defined what Gospel poverty is not, we can now say precisely what Gospel poverty is. First, we remember 1 Corinthians 2:9: Nothing compares to our God, and to what awaits those who love Him. That is, God ought to be our focus and nothing else. As Fr. Dubay writes, “Happiness is found not in things but in persons and especially in the Divine Persons…We are to be head over heels in love with God… People in love are not much concerned with things. They are person oriented, not thing centered. A consumerist is not in love.” Since love for people and for God particularly ought to be our focus, a desire for things can only hinder us in the pursuit of relationships with people and God.

Jesus reiterates this in Luke 16:33, when He said, “No one can serve God and mammon.” Note that there is no compromise here; Jesus is not asking that you serve God mainly while serving mammon sometimes. He is asking instead for a “totality of pursuit,” that is, He is asking that we give him everything at all times. To do this we need to be detached from all we possess just as we need to love with our entire selves.

To be detached, we need to view possessions in their proper place. Too often we see them as ends in and of themselves when in fact they are merely means to greater ends. John 4:34 and Colossians 3:1-2 indicate that those focused on the kingdom see all things as means only, because Earth is not our home. We are strangers, nomads, and as Hebrews 11:13-16 says, “pilgrims in search of our real fatherland in heaven.” This is a radical teaching in the society we live in. Fr. Dubay recognizes this, yet does not shirk the call to poverty. He writes: “Understanding Gospel poverty perfectly requires a perfect conversion, a 180-degree switch from worldliness.” In this there is no compromise. If we cannot accept the ideas of the Gospel, we cannot hope to live a lifestyle of factual frugality.

It seems then that we are called to poverty, but why should we be happy about it? The world associates poverty with unhappiness and wealth with happiness, and so many feel that in order to achieve happiness some type of compromise is necessary. As Fr. Dubay says, “By all standards of this world these four words [‘Happy are you poor’] are intolerably false. They seem to be an insult to the billions of human beings at this moment enduring the slow, grinding torture of empty stomachs, cold nights, crawling vermin, lingering insecurity, gnawing idleness, premature death.” Despite the fear such images invoke in us, we must learn to be poor in spirit and in fact.

Material wealth and the pleasures of the world only leave us more dissatisfied. The Gospel is not easy, for it calls us to a paradox: we must embrace a certain asceticism but also a rich, abundant life in Christ. To do this we must make Gospel poverty concrete in our daily lives so that to others Gospel poverty translates factually as well as spiritually. So the question, especially for the laity and those who must support a family, is how to do this practically? If factual poverty is not hunger or destitution, what is it?

It seems too hard for us to embrace the poverty of St. Francis of Assisi, but Scripture about poverty (as does all Scripture) applies to every person in every vocation, including the married or single as well as priests and religious. This seems “outrageous” to today’s world, Fr. Dubay admits… and yet, “frugal living is a religious ideal,” one we must all desire.

So what can the laity do? Fr. Dubay lays out several guidelines for the laity to achieve what is required by Gospel poverty. The first is to have “Value Motivation,” which means that we must pursue poverty for the right reasons, namely for what poverty makes possible: a “radical readiness for the divine word,” the “freedom to live a sharing-sparing lifestyle” and “apostolic credibility.”

The second is to maintain one’s state, that is, to avoid superfluities without neglecting one’s duty to one’s family. To do this, it is very helpful to look to the lives of the lay saints. St. Thomas More and Elizabeth of Hungary provide great examples. St. Thomas More was known to spend lavishly only on two things: the education of his children, and a zoo that he kept both for study and because he knew that his children and visitors were greatly entertained by the animals. St. Elizabeth of Hungary spent money on dresses, but only because she saw that seeing her wearing them greatly pleased the husband to whom she was devoted. She still managed to use much of her time and money helping the poor and so managed to be a sign of Gospel poverty to the world.

It is very important that as we live the Gospel poverty, we serve a sign of poverty to the world and challenge its preoccupation with possessions. To do this our poverty must be visible through a simple lifestyle that contrasts, even clashes with the status quo of the world. As Dubay writes, “The deeply converted layman is different from the large majority of his counterparts. He is a challenge in the flesh. Not that he preaches daily homilies in shop or office. But he must be different—and not all will like the difference. Though he is living in this world, his center of gravity is not on earth; it is in the bosom of the trinity.” This sort of life is what Dubay refers to as “Saintly Radicalism,” which means offering countless small sacrifices each day. That might mean skipping your customary cup of coffee, or taking a cold shower or giving up anything which, offered as a sacrifice, could help you focus on God. The best way to see how to do this is to examine the lives of the saints, especially the lay saints, and to practice serious self-examination.

Self-examination is neither popular nor easy, but it is essential to spiritual growth. One of the best ways to examine our lives is to learn to identify things as either necessities or superfluities. The things we buy and own may or may not be necessary depending on what our goal is and where our center lies. If our goal is with God, then things are necessary if and only if they help us to grow closer with God. That which is necessary can be divided into two categories: ends and means. Ends are things sought for because they are good in themselves and nothing can justify being without them. Examples include God, knowing, and loving. Means are necessary only when we must have them to reach one of the aforementioned ends.

A superfluity, on the other hand, is needed neither for itself nor as a means to an indispensable end. As Fr. Dubay puts it, “Pursuing a superfluity is pursuing a dead end.” To live Gospel poverty we must then rid ourselves of superfluities and concentrate on those things which are necessary for union with God. To do this we must ask ourselves a few questions. Fr. Dubay offers sixteen of them, but a few really stand out:

“Am I happy when at times circumstances require me to go without a necessity?” For example, when things break, like the hot water heater or our computer, do we curse about the burden or do we thank God for the opportunity to live more simply?

“Do I give to the poor not only from my superfluities but also from my need?” Jesus said that the woman who gave her last penny away was the most blessed. We need to ask ourselves if we are following that example, or if we only give what we can spare.

“Have I practically [in practice] embraced the consumerist philosophy of ‘the good life’? Do I consider myself as called to witness against this philosophy by a sparing-sharing manner of life?”

“Am I vain in my dress…my home…my other possessions?”

“Can I conclude from my manner of life that my center of gravity is not in this world? Does my use of creation speak of God to them?”

In closing, the exercise of the virtue of poverty, as outlined in the Gospel and evidenced in the lives of the saints, naturally flows from all we have come to know and understand in our faith. We cannot, in good conscience, ignore this crucial element of the Christian life, because we cannot achieve true holiness without it.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)